M31: Can one star change the universe and the course of science?

I have been saying for years that every photograph of the cosmos, even the seemingly uninteresting ones, contains a hidden “secret”. M31 is probably the most amateur-photographed object in the night sky. So exploited and postcard-perfect that nobody clicks on it anymore. I purposely didn't name the article “M31” – I like it when people read or look at what I write. So what's interesting about the next M31 image?

Andromeda Galaxy and Great Debate: How can a simple star change the course of the history of science?

There's this big revolution in science (and beyond) that most people learned about at school, but rarely pay attention to it when they look at Andromeda galaxy images on the Internet.

Like any revolution, it began with a fight. The conflict was not over a small thing, but over the size of the cosmos. In 1920, two eminent astronomers argued on a train on a 4,000-kilometre journey somewhere between California and Washington: Harlow Shapley and Heber Curtis.

Shapley was convinced that our galaxy was the end of the universe, which at the time was thought to be about 100,000 light-years long. Curtis, on the other hand, who was studying a blurred “nebula” (now called the Andromeda Galaxy), was certain that it wasn’t part of our galaxy, but a completely separate “island universe”, containing billions of stars.

The conflict spread to the official astronomy conference at the Natural History Museum, where the two scientists met. The public debate went on day and night. Today, the world remembers this event as the Great Debate.

It should be kept in mind that not everyone was happy with the steady process of weakening the divine Earth’s position in the universe. Not only had Copernicus sealed the central position of the Sun in the Solar System, but now the Earth, the Solar System and the entire Milky Way were to be knocked out of their central position in the universe. Scandalous!

Curtis attacked with very precise arguments. As he pointed out, the Andromeda Nebula is lit up by exploding stars, just like our own galaxy. What makes them drastically different is their lower brightness. He concluded from this phenomenon that they must be much further away than the stars in our galaxy, which are much brighter. M31 is therefore a galaxy and not just another nebula in the Milky Way. Despite such an overwhelming vision and strong evidence, few were convinced by Curtis at the time.

Check also:

- The Earthrise Photo: A Journey Through Earth’s Iconic Space Portrait

- William Bill Anders Tribute: Astronaut, Earthrise Photographer, Aviator

Pale Blue Dot Image: What About Large Format Prints like Fine Art?

JADES-GS-z14-0: NASA's JWST Discovering the Most Distant Galaxy

Hubble Telescope Captures a Stellar Trio: The Dawn of a Sun-like Star

AT2018fyk: the star survives a close encounter with a black hole only to meet it again

First known binary system composed of two Y-type brown dwarfs

Magellan shows volcanic activity on Venus – VERITAS mission to investigate

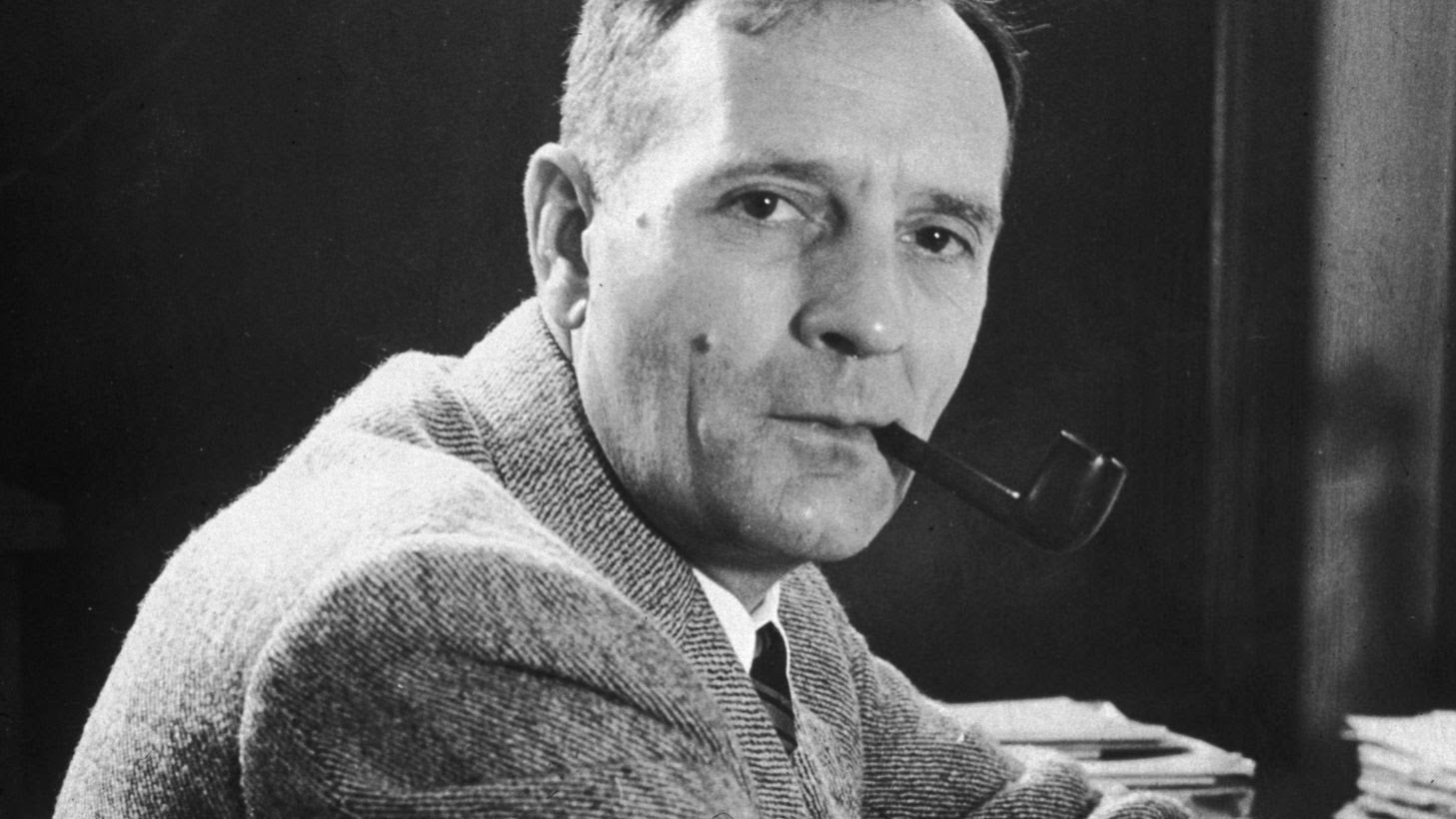

Andromeda Galaxy (M31): Edwin Hubble's contribution

Only four years later, Edwin Hubble took the legendary photograph of the Andromeda Nebula, after which it eventually became the Andromeda Galaxy, and the author himself made history. It’s hard to find such a photograph that has changed human history so much.

Although young Edwin didn't have the equipment with sufficient parameters to resolve the galaxy into individual stars, he did something far more spectacular and with greater power of evidence.

In his photograph, Edwin spotted three new stars. He labeled them with the standard for novae “N” mark and compared his photo with others from the Mount Wilson archive.

The astronomer quickly concluded that one of the stars was not a nova, but a Cepheid variable. He crossed out the “N” and wrote down probably the most famous correction in the history of science: "VAR!".

Studied by Henrietta Leavitt, the Cepheids became a kind of radio beacons that completely changed the overall picture of our galaxy. We owe them the ability to estimate the distances of stars beyond the reach of other methods, such as parallax measurement. This is how humanity saw the true scale of our galaxy.

This is what Hubble understood and started doing the calculations. Using simple arithmetic, he proved that the Cepheid variable was nearly 1 million light-years away from Earth. Given that the estimated size of the galaxy at the time was 100,000 light-years, it was a shocking value (today we know that this value is 2.5x larger).

Thanks to Edwin Hubble's discovery people found the Milky Way was not the only island in the universe.

What more spectacular discovery could an astronomer make?

Read more:

- Nili Fossae: Explore the Legendary Scars of Mars

James Webb Space Telescope uncovers young stars in NGC 346’s dusty ribbons

Enceladus holds potential for alien life with recent discovery of vital element

Anticipating the celestial show – Betelgeuse's potential supernova event

Supernova 2020eyj: First radio signal from the massive explosion of a dying white dwarf

Messier 31 (M31): A star from 2.5 million years ago. How I made my photos?

At this point, a question that arises in every space enthusiast's mind is: which star is it all about?

I wasn’t surprised to learn that it was simply named “Hubble variable number one” or V1 for short. What is surprising, however, is that it can be seen in many “entertaining” photos of M31 that you might see on the Internet. This is a great triumph of technology.

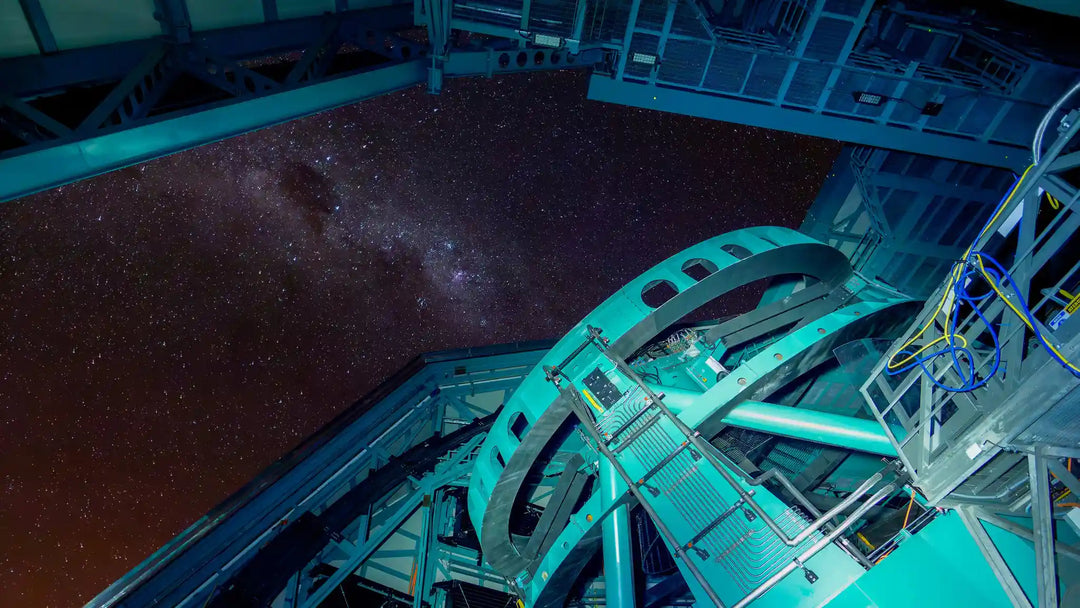

I remind you that Hubble took his image with a huge telescope with an optical diameter of 100" (2.5 meters) and he exposed the photo for 45 minutes.

Even these days, a telescope this large is beyond the reach of amateurs. But we have made huge progress in the field of detectors (CCD/CMOS sensors). Images of even much greater scientific, cognitive and aesthetic quality, can now be taken with a small telescope. I took my photo from a suburban garden with a 6" diameter telescope (0.15 meters).

To image a single star, clearly separated, from a distance of 2.5 million light-years – satisfying. To make photometric measurements and record its variability by yourself, then repeat Edwin Hubble's arithmetic and calculate its distance? For an amateur astronomer – priceless, wonderful, magnificent. And this is exactly my plan. I’d really like to start collecting photometric data on this Cepheid in August and use it to determine its distance. Just a small dream.

A photo of M31 taken by me with a much larger telescope (0.5m diameter). Unfortunately, I was photographing a different part of the M31 galaxy that night and the V1 star will not be found here:

To image a single star, clearly separated, from a distance of 2.5 million light-years – satisfying. To make photometric measurements and record its variability by yourself, then repeat Edwin Hubble's arithmetic and calculate its distance? For an amateur astronomer – priceless, wonderful, magnificent. And this is exactly my plan. I’d really like to start collecting photometric data on this Cepheid in August and use it to determine its distance. Just a small dream.

A photo of M31 taken by me with a much larger telescope (0.5m diameter). Unfortunately, I was photographing a different part of the M31 galaxy that night and the V1 star will not be found here:

And for dessert, a color image of the M31 galaxy (aesthetically pleasing astrophotography):

You can buy it as an artistic Fine Art print in Astrography.com store:

“I would argue this is the single most important object in the history of cosmology” – David Soderblom, Space Telescope Science Institute, Baltimore.

What do you think about all of this?

References

- Andromeda Galaxy M31, Science NASA, [24.04.2024]

- Cepheid variable, link, [24.04.2024]

- Henrietta Swan Leavitt, Britannica, [24.04.2024]

- Howwel E., Henrietta Swan Leavitt: Discovered How to Measure Stellar Distances, Space.com, [24.04.2024]

- Hoskin M. A., The 'Great Debate': What Really Happened, Journal for the History of Astronomy 7 (169-182), link, [24.04.2024]

- Hubble's Famous M31 VAR! plate, Carnegie Observatories, [24.04.2024]

- Messier 31, Science NASA, [24.04.2024]

- Shapley, H.; Curtis, H. D. (1921), "The scale of the universe", Bulletin of the National Research Council. 2 (Part 3, Issue 11): 171–217, link, [24.04.2024]

![Vera C. Rubin Observatory: Revolutionizing Astronomy Through the World's Most Advanced Telescope [All You Need To Know]](http://astrography.com/cdn/shop/articles/vera-c.-rubin-observatory_main.webp?v=1751627507&width=1080)

Leave a comment